83 Black Holes Found at the Edge of the Universe

International astronomers have made an incredible discovery recently that many may not see the significance of right away. Astronomers discovered 83 supermassive black holes on the edge of the universe. There’s a lot to unpack from that simple statement, but the discovery remains the same. After all, astronomers were pretty confident we wouldn’t find black holes in these far-reaching places, but now we have 83. So, let’s jump into an explanation and try to figure out the basics.

What Does This Mean?

Let’s start by taking apart the black holes. A supermassive black hole is often found in the center of a galaxy, like the Milky Way, and are extremely hard to see using a telescope. After all, black holes put off absolutely no light. The better term is that astronomers have found 83 quasars, which are powerful explosions of gas that are believed to occur right outside the event horizon of a supermassive black hole. Next to supernovae and gamma-ray bursts, quasars are the brightest things in the universe.

Now let’s tackle the idea of the universe having an “edge.” There is no real edge of the universe. What astronomers mean is that these suspected black holes were found about 13 billion light-years away. We also believe the universe is about 13.82 billion years old, meaning we think the Big Bang occurred about 13.82 billion years ago. In other words, these black holes have existed less than a billion years since the universe’s birth.

So now the point of this article suddenly takes on a different tune. Astronomers found that 83 possible quasars existed when the universe was still extremely young. Considering we initially thought black holes came about as the universe aged, this is a huge deal.

How Did We Find the Quasars?

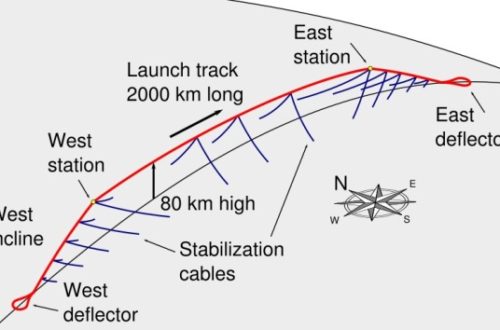

Japanese astronomers were the first to discover the quasars with the Subaru Telescope stationed in Hawaii. Using the very powerful Hyper Suprime-Cam or HSC, astronomers looked to the darkest parts of the sky for five years. During those five years, they found quasars and allowed us a peek into a black hole’s origins.

The Subaru Telescope is 8.2 meters in diameter and held the record for the largest monolithic primary mirror until 2005. Because of the size, the HSC is taller than a human and weighs about three tons. With 870 megapixels in a 1.5-degree field of view, astronomers were confident that if there were black holes this long ago, they could find them with this particular telescope.

Scientific Impact

Team leader Yoshiki Matsuoka of Ehime University in Japan said, “it is remarkable that such massive dense objects were able to form so soon after the Big Bang. The most distant quasar discovered by the team is 13.05 billion light-years away, which is tied for the second-most-distant supermassive black hole ever discovered.” Matsuoka and the team found that there was about one quasar and suspected supermassive black hole a billion light-years apart, side by side.

The quasars are basically galaxies in the early universe. The difference between these ancient galaxies and the ones we’re familiar with today is the activity and number of the black holes. These distant quasars are numerous and extremely active compared with the relatively quiet supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies like the Milky Way. Before this discovery, it was unclear when supermassive black holes first formed and how many exist. Today, the answers still aren’t obvious, but we have a lot more information about their formation and how far they date back than we used to.

Changing Our Understanding

The biggest piece of knowledge to come out of this discovery is the sheer scope of how much we don’t know. These quasars show us there’s a lot about the universe we don’t understand. We have plenty of theories but humanity may never know the entire nature of the universe for certain. Every day, we’ll learn something new and understand the cosmos a little more. Discoveries will also lead to more questions and encourage more exploration. We might not have the answers now, but we’ll still looking to the night sky in awe.

Would you like to receive similar articles by email?